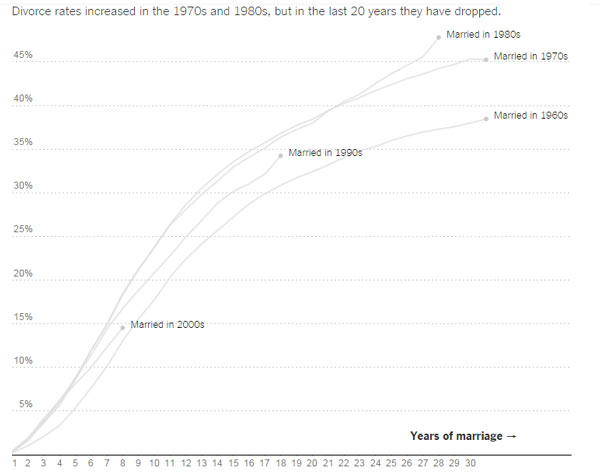

Cumulative share of marriages ending in divorce

When Gwyneth Paltrow and Chris Martin “consciously uncoupled” this year, ABC News said it was the latest example of the out-of-control divorce rate, “50 percent and climbing.”

When Fox News anchors were recently lamenting high poverty levels, one of them blamed the fact that “the divorce rate is going up.”

And when Bravo introduced its divorce reality show, “Untying the Knot,” this summer, an executive at the network called it “a way to look at a situation that 50 percent of married couples unfortunately end up in.”

But here is the thing: It is no longer true that the divorce rate is rising, or that half of all marriages end in divorce. It has not been for some time. Even though social scientists have tried to debunk those myths, somehow the conventional wisdom has held.

Despite hand-wringing about the institution of marriage, marriages in this country are stronger today than they have been in a long time. The divorce rate peaked in the 1970s and early 1980s and has been declining for the three decades since.

About 70 percent of marriages that began in the 1990s reached their 15th anniversary (excluding those in which a spouse died), up from about 65 percent of those that began in the 1970s and 1980s. Those who married in the 2000s are so far divorcing at even lower rates. If current trends continue, nearly two-thirds of marriages will never involve a divorce, according to data from Justin Wolfers, a University of Michigan economist (who also contributes to The Upshot). There are many reasons for the drop in divorce, including later marriages, birth control and the rise of so-called love marriages. These same forces have helped reduce the divorce rate in parts of Europe, too. Much of the trend has to do with changing gender roles — whom the feminist revolution helped and whom it left behind.

“Two-thirds of divorces are initiated by women,” said William Doherty, a marriage therapist and professor of family social science at University of Minnesota, “so when you’re talking about changes in divorce rates, in many ways you’re talking about changes in women’s expectations.”

The marriage trends aren’t entirely happy ones. They also happen to be a force behind rising economic and social inequality, because the decline in divorce is concentrated among people with college degrees. For the less educated, divorce rates are closer to those of the peak divorce years.

Of college-educated people who married in the early 2000s, only about 11 percent divorced by their seventh anniversary, the last year for which data is available. Among people without college degrees, 17 percent were divorced, according to Mr. Wolfers.

Working-class families often have more traditional notions about male breadwinners than do the college-educated — yet economic changes have left many of the men in these families struggling to find work. As a result, many wait to achieve a level of stability that never comes and thus never marry, while others split up during tough economic times.

“As the middle of our labor market has eroded, the ability of high school-educated Americans to build a firm economic foundation for a marriage has been greatly reduced,” said Andrew Cherlin, a sociologist and author of “Labor’s Love Lost: The Rise and Fall of the Working-Class Family in America.” “Better-educated Americans have found a new marriage model in which both spouses work and they build a strong economic foundation for their marriage.”

Some of the decline in divorce clearly stems from the fact that fewer people are getting married — and some of the biggest declines in marriage have come among groups at risk of divorce. But it also seems to be the case that marriages have gotten more stable, as people are marrying later.

Ultimately, a long view is likely to show that the rapid rise in divorce during the 1970s and early 1980s was an anomaly. It occurred at the same time as a new feminist movement, which caused social and economic upheaval. Today, society has adapted, and the divorce rate has declined again.

In the 1950s and 1960s, marriage was about a breadwinner husband and a homemaker wife, who both needed the other’s contributions to the household but didn’t necessarily spend much time together. In the 1970s, all that changed.

Read the full article: NewYorkTimes.com